THE MAD-HANDBALLERS’ TWEAK-EMPORIUM SERIES by Boak Ferris

WPH Press, Tucson, AZ

THE MAD-HANDBALLERS’ TWEAK-EMPORIUM SERIES

Part 1. WHAT TIME IS IT? LEARNING YOUR CLOCKS!

By Boak Ferris

If you the mad-handballer “scientist” be, you may find this intended new series a go-to treasure trove of fun tweaks to test in your daily drills. As a mad scientist myself, during dark days and nights, when no competitors appear, I visit an empty stadium, to test the many different moves exhibited by elite champions, and also to test other moves only imagined—or hypothesized. What might happen to my game and shots if I did “X”? Of if I combined “X” and “Y” with “Z”?

In my case, what I search for is “the perfect feel with the desired trajectories.” The perfect feel equals the perfect contact, with the finished shot going exactly where I intended—with all my leverage and rotation delivered, with no stumbles or subsequent dissatisfaction. Working on feel is one way to practice and develop FLOW, which is ordinarily difficult to train. FLOW may be the gold at the end of the rainbow for athletes everywhere?

In your case, however, you might be seeking more power. Or maybe better stability and balance when you reach the pre-shoot position; or maybe even a better more reliable weight-transfer? Most likely, however, handballers wish to prioritize ways to earn more points and sideouts, and to lose fewer points and service opportunities. Each gained inning might be tantamount to 3 to 6 more points in the score differential; while each saved service inning might be equally valuable.

CLOCK 1: THE HUMAN BODY CLOCK; EXPLOITING OPPONENTS’; LEARNING YOURS

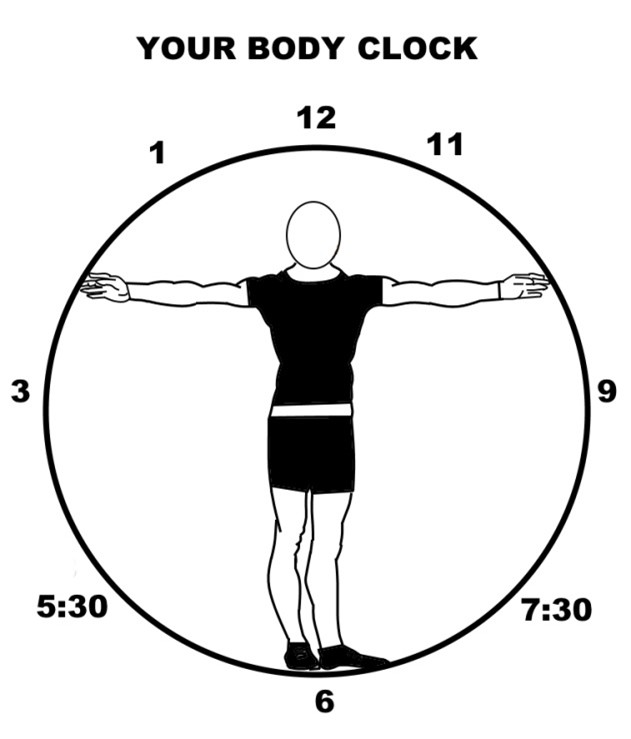

Please visit the diagram below. As you can see it represents a handball player facing toward the viewer.

Today’s lesson about body-clocks comes from Chapman who learned it from Coach Lew Morales. Every right-handed pro player is very strong at clock-hours 12-6, with some being unbeatable at certain clock hours, such as Lucho Cordova being indomitable within the 4-5:30 range on his personal body clock. He is a genius at moving to a pre-strike position that allows him to address the ball at right around 4:30. Martin Mulkerrins is inordinately powerful between 3:30 and 4:30, especially if he can hit the ball at those heights after placing his front foot down. Fink is amazing between 7 and 8: why would I ever send a ball to his 7:30? Brady wants the ball at 5, and will sprint to the court board that will allow him to strike it at that preferred height.

To return to Chapman, however, and how understanding the body-clock became important for winning championships, please remember that in 1992 TGO griped about losing to John Bike’s blazing left-handed kills and sizzling passes. Lew’s answer? “Well, you are going to lose if you keep feeding your shots to his left between 6:30 and 8:30, where he kills or passes it, with joy and pleasure.” (“But Lew, the match took place at 4 PM!”) Lew continued, “You’ve got to learn to get the ball to his 12:30 or 1 On His Body-Clock—WITH EVERY SHOT. (That meant sending the ball to Bike’s very professional and good right overhand.) “Or at the very least,” Lew continued, “aim to loft a speed-controlled bounce-pass slider between the wall and his 3, if you cannot go up.”

As boring and repetitive as these two shots sound, TGO started lob-serving Bike’s right hand, and working to return every rally shot high to Bike’s right at the 1 O’clock height, until he earned an overhit from Bike, and got the backwall setup he needed. TGO started seeing Bike as “The hole at 1 O’clock; with the back-up bounce-pass slider hole at 3.”

The benefits of understanding the opponent’s Body-Clock are two-fold.

First, every player is weaker at certain clock-hours, and if you wish to level-up your game, you need to master the mechanics to get all of your shots, whether left-handed or right-handed, to any specific opponent’s weakest hours. To improve your pre-match preparation, your first thoughts should be, “I’m playing opponent X today; what are his two weakest hours, and can I get every ball there?” To gain this knowledge, you and your team might need to do some video-watching or on-site scouting, what all professional teams do. This thinking about the opponent’s clock is especially true on defense, when you are receiving serve, and cannot afford to gamble, without risking giving a free point. [As a coach and scout, one of the first things I look for is whether a competitor gambles on defense, going for a low percentage, aiming at the floor. As soon as I see that, I tell my clients, “That’s losing handball, where pride and greed overcome cool and control. Such players can usually be tempted by sending, or fishing with, grapefruits sent to the rear corners.”] Why let the floor become your opponent’s teammate?

TGO even said, “Keep it simple: when in doubt, hit it to your opponent’s off-hand”—basically, hit it to the weak-side of the clock, like going for a layup against the weaker defender, or sending a football play to the other team’s weaker side: common strategies in professional, high-paid sports. In handball, of course, the pay is more points, prestige, and ultimately aura, worth five points a game.

Second, you yourself are strong at certain clock-hours, and weak at others. If you wish to level-up, you need to repair your clock-hour holes, like learning to hit your weak-side ceiling balls back up to the ceiling or front wall along the same side. You rarely need to drill your best shots, no matter how good they feel, or how much they reward your need for control; what you need to repair are your weakest shots and foot-and-elbow moves. If you have certain strengths at certain clock-hours, then, by all means, you need to play rallies and move your feet, and prepare your arms, so you can address the ball right at your favorite hour. Truly, mastering the Body-Clocks is more about self-knowledge, backed up by proof: deliberate extra footwork, pre-shoot positioning, preparation, visualization, lifting the elbows for an early pre-swing, and then calm deliberate execution—adding a millisecond lag to stutter or wrong-foot your opponent. If you consciously master the Body-Clock understanding, practice, visualization, and drills required, you will gain anywhere from 5 to 6 service innings per game per opponent. By the way, Lew once said, “If you can deliver the right shot from any clock-hour, no one can beat you. Practice all hours from the three basic court locations.”

CLOCK 2: CONSCIOUSLY “CLOCKING” THE BALL

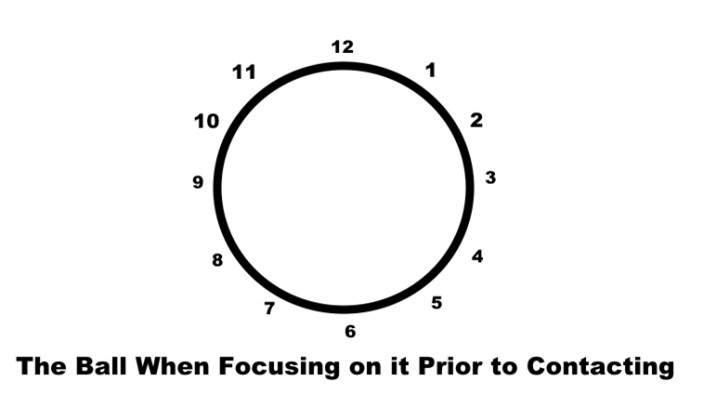

Please view the diagram:

The diagram illustrates a ball flying toward you. By assigning clock hours to it, players will start improving their eye-discipline for tracking and striking intended shots. For better, more consistent ball-striking, players will benefit to combine their body-clock self-awareness with also visualizing a clock on the ball.

As a self-centered example, I have a reliable kill-shot with my left hand, which I can hit from about the short line to the rear left 35-foot area. I have developed this response as a surprising defensive move against opponents over-playing to my left. I can do this shot automatically, simply because I see the ball really well on that side, and I get into a pre-shoot position with my elbow up, so I can swing at my body-clock at 7:30, while “clocking” the ball at its own “8”. Furthermore, I add follow-through to keep the ball down and moving low, by visualizing my hand contacting the ball at its 8, and then my hand rolling over the ball and releasing the ball at its 2 or 3. This may sound obsessive, but I did not invent these visualizations. I learned them from TGO, who created them, as far as I know, transferring what he learned from Coach Lew, to his ball-perception. Arguably, he saw the ball better than anyone in the history of handball.

For another example, consider Brady’s power reverse serve to the left. As Brady works his feet in the service zone, he has practiced incessantly to drop the ball in such a way that it drifts toward the front line, in tandem with his front foot, arriving there together. As the ball falls in front of his planting left toe, he releases his rear foot and hip, and strikes the serve at around 5:30-5:45 on his (standing) body-clock. But he also clocks the ball at its 6 at the base of his palm below his little finger, allows the ball to roll through his palm as he turns his wrist over, to release the ball off his first, middle, and ring fingers. His right hand follows-through between his left shoulder and left cheek, as he posts up and around his front leg. The ball does not leave his hand until he has rolled it from its 6 to its 10. (Please note that the perceived hours on a pre-struck ball will “move,” respective to your view of the ball, as you strike it, and as it rolls through your hand. So, to keep nomenclature simple, we simply need to keep the same relative clock-face of the ball in our mind, as in the illustration above, even as the ball rotates.)

Where you clock the ball at contact, and where your hand ends up on the ball’s clock as you release it, these are both integral parts of your personal power, accuracy, and control. If you have less personal power, you will want to learn the clock-part of the ball you need to contact to loft and place your passes, hit your ceilings, or drive your kills and punches, or roll your paddles. If you have a lot of torque cycling from your plant, through your hips, torso, elbows, and into your front step, where you add “posting” to catapult with extra pop, your preferred Body-Clock contact points and Clocked-Ball contact points will differ from opponents’.

By learning and selecting the appropriate hours on the ball, for defensive shots—and also for offensive shots—your eye-discipline will improve overnight, your errors will diminish 100 %, your accuracy will improve, your sense of satisfaction and control will upgrade, and you will start gaining innings. If you practice.

Now, please allow me to close with a few more professional examples.

TGO had an amazing, right-handed, punch-bounce-pass reverse to the left, which he started developing when he was 16. As he matured, he learned to address the ball at 4:30 on his body-clock, and clock the ball on its 5. Unseen, however, is that he turned the ball over (or around) on his fist, until his knuckles reached the ball’s 12 O’clock, causing the ball to have some reverse spin. He also had a front-wall target, but he did not need to look at that, since it wasn’t moving. Similarly, he knew that opponents would protect against this punch-pass, so he mixed in a dominating right-hand-paddle to the right corner or right front wall, using a pendulum swing and contacting the ball near his front ankle at his body clock at almost 6. Unseen, however, is that he practiced and practiced his paddle, until he could contact the ball at its 6:30 or 7, imparting a bit of inside out! Clocking the ball at that hour kept the ball low, moving away, and toward the right, where he could block the opponent’s access to the shot with his body. Once he had mastered the two clocks, as above, he could mix in paddles to go straight in up the right, or to go cross court to the opposite left corner outside-in. All he needed to do during practice was combine the perfect body-clock address with finding an exact hour on the ball. (He does not tell you this in his instructional, of course!) The result? Unbelievable shot-making, eye-discipline, sure-hands, control, and won-matches.

As another example, when he was young, he had a rather weak left overhand. To prevent opponents from scoring against his weaker 11 O’clock, he developed a combined body clock/clocked-ball reply. He moved to address the ball closer to his body’s 9, and then clocked the ball at its 8, rolling it counter clock-wise through his hand and having his fingers leave the ball at its 5. (Lew and I used to call this defensive shot, “Slinging the ball.”) He could contact the ceiling with backspin with this shot, while few opponents could exploit him. In this case, he protected a known body-clock weakness, with footwork, and body-clock/clocked-ball knowledge.

Now, one last example. Brady has developed an amazing and devastating defensive body-clock shot at his 9. If the opponent hits the ball to his left, and if he sees he has time to move his feet to address it at his 9, he snaps his elbow up, makes space, and then clocks the ball at its own 9 or even 10. He usually rolls it through his hand to add spin and velocity, and the ball leaves his hand at its 3 or 4. He can go sidewall front-wall, hit it straight in, or bounce-pass it hard through the center or toward the right, all by leveraging position to exploit his body clock, and to exploit his superior eye-discipline to CLOCK THE BALL.

So, as soon as you know what time it is; MOVE YOUR FEET.

Thank you to Boak Ferris for discussing Learning Your Clocks

View all of the WPH Coaching Centers HERE

Be sure to Like, Subscribe, and Share WPH Coaching Centers